I remember a scientist saying that many of the amphibians

around the world are going to go extinct and that it would be better to stop

extreme conservation efforts and, rather, study these species so that we will

know what we have lost. What we are

losing. I think this scientist was

speaking from a dark place in the face of unprecedented declines. In other words, he wasn’t in his happy place.

For those of us who love the natural

world, it is sometimes hard to find *that* place where we can be filled enough

with curiosity and wonder to prevent our knowledge of biodiversity loss

trespass into the moment.

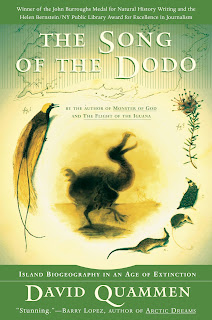

I just started reading The

Song of the Dodo (1996) by David Quammen with some other folks in the

department—I predict we are going to a dark place eventually, but we are not

there yet. What has struck me most is

the journey of Alfred Russel Wallace into the Amazon then onto the Malayan

Archipelago. Or maybe it is simply

Wallace who strikes my fancy. In modern

times he would be a first-generation college student. He does not profit from family wealth or

connections, but rather from sheer skill, determination, and tenacity—and a

little luck, both bad and good. It was

enough. As he struggled to figure out

how to explain the relationships between species on islands and the mainland,

he reached out to his more privileged mentors who sometimes helped him, but who

also may have taken advantage of his professional naïveté. By all rights, Wallace could have scooped

Darwin and had he been a little more competitive, perhaps Darwin would be the

parenthetical scientist. Wallace clearly had a more focused vision of

what he was looking for when he headed out to study islands than Darwin had

when he was collecting his mockingbirds and finches willy-nilly, it turns out,

in the Galapagos, failing even to label the islands his specimens came

from. (Given that Captain Fitz-Roy and Darwin’s

manservant had labeled *their* collections, one does wonder how young Darwin

could have been so lackadaisical. Those of us who have made mistakes in

science, however, should sympathize and forgive—I suspect we have all kicked

ourselves more than once…and the heat of the field season can cause a poor decision

or two.)

Wallace’s (and Darwin’s) world was already missing pieces of

the biological puzzle, although they had not fully grasped that extinction was

a grim reality as they bagged animal after animal to sell and to study. They were already part of the beginning of

the sixth extinction even if their world was much less trampled then. Even if

we could travel back in time to whisper in Wallace’s ear of what is to come—to offer

warnings of caution and restraint—should we?

If biodiversity was doomed with the evolution of humans, as Elizabeth

Kolbert suggests in The Sixth Extinction and

as a good look around would bolster, then perhaps my gloomy colleague was right:

best to study these species now to know what we have lost. In which case, we forgo the challenge of time

travel, except for what we find in these pages of history and in the natural

history museums that proffer a glimpse back into a world we will never put

quite back together. A glimpse offered

by the likes of Wallace and others who better recorded what was found, and

seen, and heard, than any who glimpsed a dodo.

Enjoying the magic of David Quammen’s writing and wondering

to what point of despair we are now headed as we read into “The Rarity Unto

Death.”

No comments:

Post a Comment